Police Response to Students in Emotional Crisis: A Call for Comprehensive Mental Health and Social-Emotional Support for Students in Police-Free Schools

This report explores data on police responses to more than 12,000 “child in crisis” interventions, where a student in emotional distress is removed from class and transported to the hospital for psychological evaluation. A disproportionate share of these interventions involved Black students, students attending District 75 schools, and students attending schools located in low-income communities of color. We call on the City to end the criminalization of students in emotional crisis by eliminating police from schools and investing in behavioral and mental health supports and services.

On June 3, 2021, Advocates for Children of New York (AFC) released a new data brief, Police Response to Students in Emotional Crisis: A Call for Comprehensive Mental Health and Social-Emotional Support for Students in Police-Free Schools, exploring data on police response to more than 12,000 incidents between July 2016 and June 2020 involving a student in emotional distress removed from class and transported to the hospital for psychological evaluation—what the New York Police Department (NYPD) terms a “child in crisis” intervention. Mirroring broader trends in policing, a disproportionate share of these interventions involved Black students, students attending New York City Department of Education (DOE) District 75 special education schools, and students attending schools located in low-income communities of color. The brief calls on the City to end the criminalization of students in emotional crisis by eliminating police from schools and invest in a comprehensive, integrated system of school-wide, multi-tiered behavioral and mental health supports and services that will promote well-being and equity for all students and school staff.

The new brief is an update to AFC’s November 2017 report, Children in Crisis, which examined NYPD data on such interventions during the 2016-17 school year, the first full year for which data were publicly available pursuant to the Student Safety Act. In subsequent years, the number of child in crisis interventions only increased: during the first three quarters of the 2019-20 school year—the months prior to the closure of school buildings due to COVID-19—the number of child in crisis interventions was approximately 24% higher than the equivalent time period in 2016-17. Overall, almost half of all interventions during the past four school years involved children between the ages of 4 and 12, and in 297 instances, the NYPD handcuffed a student who was under the age of 13, including three 5-year-olds, seven 6-year-olds, and 23 7-year-olds.

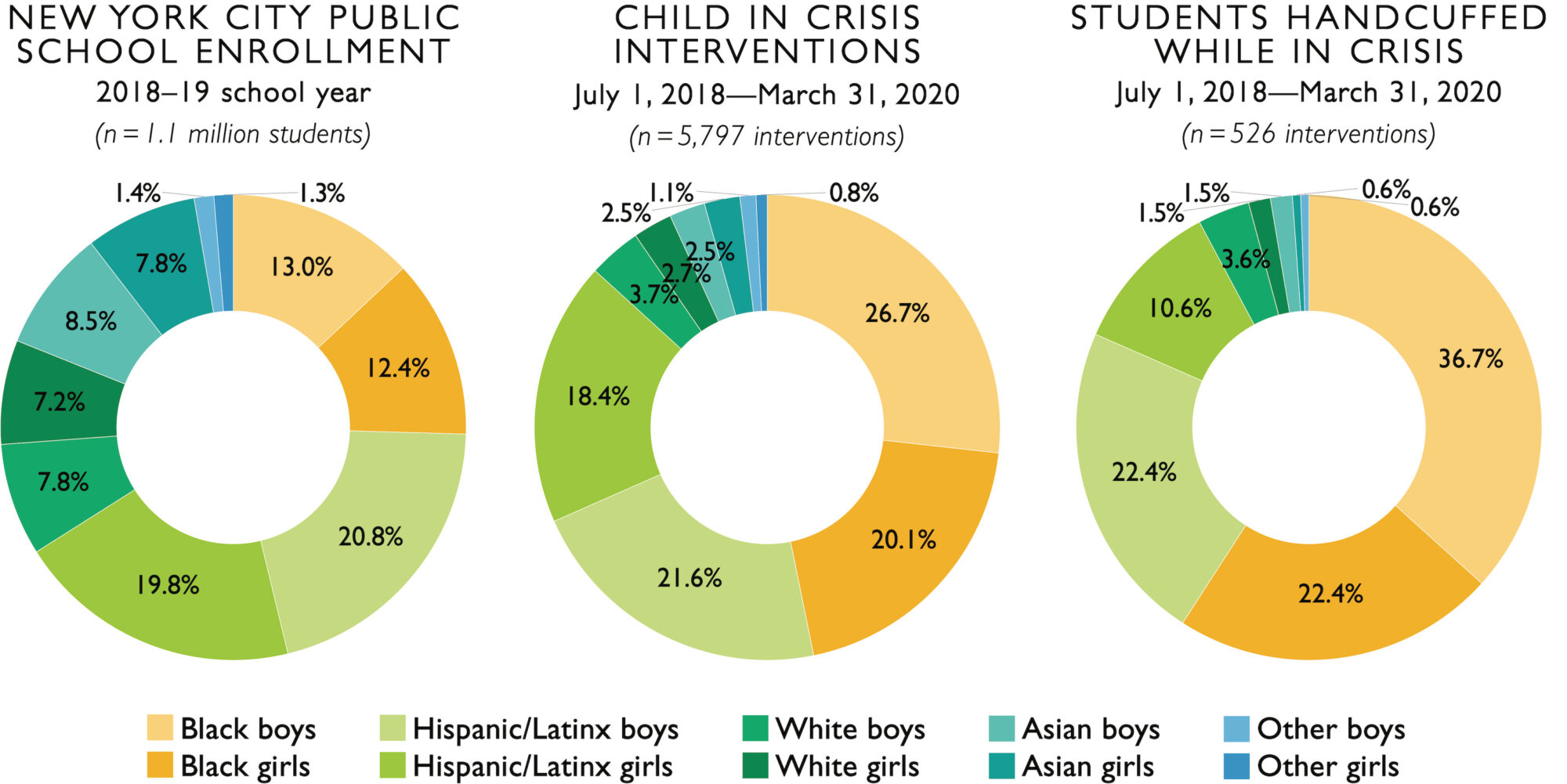

Our analysis finds that Black students—particularly Black boys—and students with disabilities attending District 75 special education schools are dramatically over-represented in the population of students for whom an emotional crisis at school leads to an interaction with the police and removal to the hospital emergency room, as well as those handcuffed during these incidents.

Between July 2018 and March 2020:

- More than a quarter (26.7%) of child in crisis interventions involved Black boys, who were only 13% of the public school population; Black girls comprised 12.4% of overall enrollment but 20.1% of those subject to child in crisis interventions.

- More than one out of every three (36.7%) students handcuffed while in emotional crisis was a Black boy; Black girls subject to these interventions were handcuffed at twice the rate of White girls.

- Of the children between the ages of 4 and 12 who experienced a child in crisis intervention during the 2018-19 and 2019-20 school years, more than half (51.8%) were Black.

- At least 9.1% of all child in crisis interventions occurred in District 75 schools, even though District 75 enrolled only 2.3% of New York City students. More than one out of every five (21.3%) students handcuffed while in crisis was a student with a disability in District 75.

The data also show that law enforcement intervened in student mental health crises at significantly higher rates, relative to total enrollment, at schools in the Bronx, central Brooklyn, parts of midtown Manhattan, and southeast Queens, as compared to schools elsewhere in the five boroughs. Overall, nearly a third (32.7%) of all child in crisis interventions between July 2016 and June 2020 occurred in just ten of the City’s 77 police precincts—eight in the Bronx, along with the precincts encompassing Brownsville and East New York in Brooklyn—even though schools located in those precincts enrolled less than a fifth of City students. Together, just two Bronx precincts—the 42nd and the 48th, which cover Morrisania, East Tremont, Belmont, and West Farms—handcuffed more children between the ages of 5 and 12 than all sixteen precincts in Queens combined.

“Students in emotional crisis need emotional support; they don’t need to be criminalized and handcuffed,” said Kim Sweet, AFC’s Executive Director. “As a city, we need to start treating all students as we want our own children to be treated.”

“Police responses are extremely traumatic for the student, their peers, and all school staff who witness the police intervention. It is impossible to justify the use of law enforcement when a student needs emotional and behavioral support.”

Jennifer Finn, special education teacher and member of Teachers Unite

The brief makes a number of recommendations for transforming the City’s response to children in emotional crisis and building the DOE’s capacity to provide effective behavioral and mental health supports to students. Among other recommendations detailed in the report, the City should:

- Stop calling 911, the police, or Emergency Medical Services (EMS) to take students to the hospital emergency room when medically unnecessary;

- Enact Intro 2188, a bill pending in the City Council that would significantly curtail the NYPD’s ability to handcuff students in emotional crisis;

- Hire more clinically-trained mental health staff in schools or in organizations partnered with schools;

- Include $118 million in the Fiscal Year 22 budget to fund the full implementation of restorative practices;

- Invest $15 million in the Fiscal Year 22 budget for an integrated system of targeted and intensive supports and services for students with significant mental health needs, such as through the Mental Health Continuum recommended by the Mayor’s Leadership Team on School Climate and Discipline, the City Council, and the Comptroller;

- Staff the Borough Offices and District 75 with additional behavior specialists to provide direct support to schools struggling to address student behavior; and

- Expand inclusive school program options for students with emotional, behavioral, or mental health disabilities.

“As a parent of a student with a disability and a Council Member in the Bronx, I am horrified by the idea that police are handcuffing students when they are in emotional crisis and that this is disproportionately impacting students with disabilities, Black children, and students in the Bronx,” said City Council Member Diana Ayala. “I have heard directly from impacted parents about how traumatic this experience is for their children. We must immediately pass Int. 2188, which outlines steps police must take before intervening when a student is in crisis and significantly limits their ability to handcuff these children.”

“Given the trauma that so many students have experienced over the past year and a half, it is more critical than ever that the DOE invest in public health alternatives to police interventions and 911 calls. None of us would head to a police precinct for mental health care for ourselves or our children—nor should we rely on police to address children’s emotional needs at school.”

Dawn Yuster, Director of AFC’s School Justice Project

-

View the press release as a PDF

June 3, 2021

Media Coverage

-

Role of police in responding to NYC students’ mental health crises has grown: report

-

Police interventions for emotionally distressed children on the rise in New York City public schools, analysis finds

-

Children as young as 5 years old are being handcuffed and removed from New York's schools by the police

-

NYPD removal of students from schools on the rise