Étudiants sans abri à New York, 2019-2020

The New York State Technical and Education Assistance Center for Homeless Students (NYS-TEACHS), a project of Advocates for Children of New York (AFC), posted new data showing that more than 111,000 New York City students—approximately one in ten children enrolled in district or charter schools—were identified as homeless during the 2019-20 school year. In the Bronx, approximately one in six students was homeless.

The data, which come from the New York State Education Department, show that more than 32,700 students were living in City shelters, while approximately 73,000 were ‘doubled-up’ in temporary shared housing situations. An additional roughly 31,900 public school students in New York State, outside of the five boroughs, were also identified as homeless last year, for a total of more than 143,500 students Statewide.

The number of New York City students experiencing homelessness has now topped 100,000—a population larger than the entire public school enrollment of the state of Vermont—for five consecutive years. While the 2019-20 count represents a decline of 2.2% from the prior school year, the closure of school buildings due to COVID-19 likely impeded schools’ ability to identify students experiencing homelessness, as the shift to remote learning made it less likely that schools would become aware of changes to students’ housing situations.

“The vast scale of student homelessness in New York City demands urgent attention,” said Kim Sweet, Executive Director of Advocates for Children. “If these children comprised their own city, it would be larger than Albany, and their numbers may skyrocket even further after the state eviction moratorium is lifted, The City must act now to put more support in place for students who are homeless.”

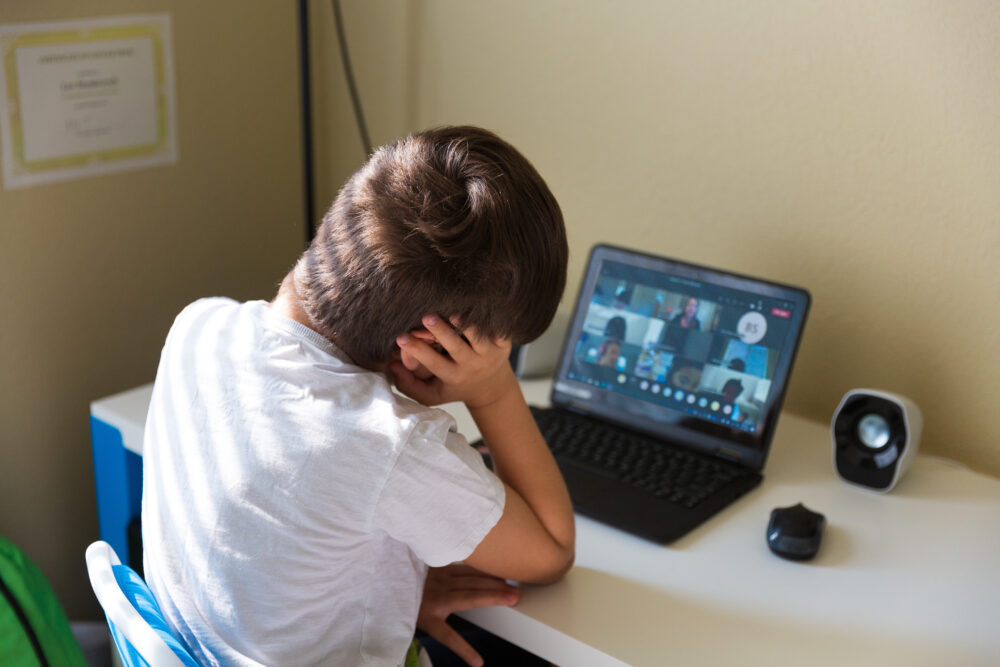

Even before the pandemic, students experiencing homelessness —85% of whom are Black or Hispanic—faced tremendous obstacles to success in school. Only 29% of those in grades 3-8 were reading proficiently in 2019, 20 percentage points lower than the rate for their permanently housed peers. COVID-19 has further magnified these challenges. For many students who are homeless, school is a lifeline—the one place where they have a sense of stability and normalcy. Remote learning, in contrast, may mean trying to complete assignments on a smartphone in the middle of a noisy and overcrowded room.

City Hall and the DOE must take action to better support these students, who are at risk of falling further behind.

- The City must ensure that every student who is homeless has the technology needed to participate in remote learning. More than eight months after school buildings closed, some students living in City shelters are still struggling to get online because their shelter lacks both Wi-Fi and adequate cellular reception to use their DOE iPad, while others have not even received an iPad in the first place. The DOE must expedite iPad delivery, install Wi-Fi in shelters as quickly as possible, and expand tech support for students struggling to use their devices, including by providing on-site support at shelters.

- The City must use attendance data to reach out to all families of students who are homeless and especially those in shelter who have not been regularly engaging in remote learning and identify and resolve the barriers that are keeping them out of school. In the spring, students living in shelter had the lowest rate of participation in remote learning of any student subgroup—more than 13 percentage points below the Citywide rate.

- The City must ensure there is adequate staff to support the education of students who are homeless. Due to hiring freezes and budget cuts, the DOE has lost more than 20 staff members who focus on serving this population. With more than 100,000 students experiencing homelessness, the City must immediately restore these positions and fully staff the team.

- The City should offer full-time in-person instruction to all students who are homeless whose families want this option, given the immense challenges so many are continuing to experience with remote learning.

- Given the months of lost learning time, the City must start planning to get students who are homeless back on track after the pandemic.

"Learning from home is much harder when you don’t have a permanent home. The City must ensure that every student who is homeless has the technology and support they need during this period of remote and hybrid learning. And as the public health situation evolves, we need to prioritize offering these students the option of getting back into the classroom full-time and providing them with the help they need to make up for lost learning.”

Kim Sweet, Executive Director of Advocates for Children

-

Consulter le communiqué de presse au format PDF

December 3, 2020